Matthew Dooley’s debut about ice cream wars in the north west of England, Flake, won the 2020 Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse prize for comic fiction, and his second graphic novel has been much anticipated. Aristotle’s Cuttlefish uses the same rundown locale – Dobbiston, and there’s another odd couple, this time, Mr Daniels, the elderly manager of the town’s lost property department, and Toby, a clueless teenager, who wanders into Mr Daniels’s orbit on work experience. Like Flake before it, the novel is unabashedly feelgood, an affectionate and very funny portrait of an unlikely friendship.

Introverted and rather eccentric, Mr Daniels dabbles in questionable theorems – the music of the spheres, and a life-extending elixir, for example – and while the structuring incongruity of Flake was the juxtaposition of dour, heavyset men and whimsical ice cream vans, here the central comic contrast is between the portly Mr Daniels in his sensible jumper and those ancient scholars of esoteric knowledge – Aristotle, Boyle, Bacon, Copernicus, Anaximander – names which summon the glamour of a long-vanished world of deep study and ardent, lofty pursuit.

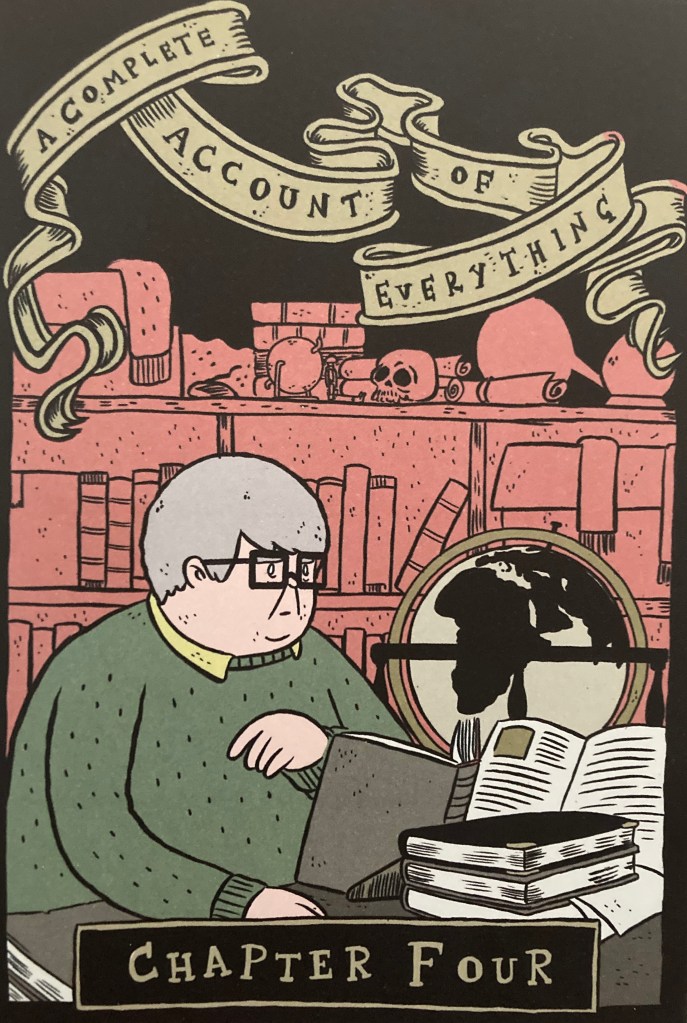

One way Dooley visually enacts that contrast is through his versions of illustrated title pages – the first chapter announces itself as ‘The Struggle Against Disorder’ – its framing the kind of architectural border which has long been relegated to literary history – complete with two puttis with moustaches and combovers. Another chapter title, ‘A Complete Account of Everything’, is printed in graphic scrolls and imposed over a drawing of Mr Daniels in a Renaissance style study, with a globe and piles of books and the obligatory momento mori skull (and several boxes of lost property). The florid ornament of such visual language is the absolute antithesis of the kind of pared down, deadpan aesthetic language Dooley himself uses, while the titles themselves, in the idiom of the Victorian sage, are similarly extravagant, their scale and vaunting ambition wildly at odds with the smallness of the lives the story depicts.

These pictorial frontispieces, and a later nod to illuminated medieval manuscripts, gesture to the larger history of visual storytelling, reminding us that the book we’re reading is part of an ongoing tradition. This has the effect of subtly historicising and de-naturalising Dooley’s own style – suggesting that his spare aesthetic language is but one iteration, one stage in the ongoing evolution of the visual book.

Dooley’s spare language might be at odds with the extravagance of past styles and past structures of feeling but there are moments in the book which partake of older aesthetic ideals. The loftiness of past aspirations to telos or an ultimate purpose or object (Casaubon’s ‘Key to all Mythologies’ a particular byword for such projects) are being gently mocked – but there is a touch of transcendence – another old-fashioned ideal – in the novel. Toby stumbles on the secret of the lost property office – an extraordinarily massive basement where Mr Daniels archives all the lost things. A later vignette explains the mystery: in the 50s a nuclear bunker was intended for another, favoured town, but a filing error meant it was built in obscure Dobbiston instead. The explanation is prosaic, but the sudden increase in scale is subtly, and rather thrillingly, expansive (1).

Dooley’s austere style also allows for moments of real sensitivity and atmosphere. A wordless double page spread shows Toby and Mr Daniels alone in their respective spaces after an argument, Toby sitting sadly in the local park by a bandstand, Mr Daniels glum in his kitchen. Toby’s tie is blown back in the wind, and three panels above track the movement of some leaves – the blown tie ensures the leaves’ movement is fully legible while the synthesis of both makes the wind palpable. The panels of leaves pair with those in the facing page tracking the darkening of Mr Daniels’ tea as it brews, testifying to time passing, while the bottom panels pan out to show the same grey sky over both the empty park and Mr Daniels’ street – reinforcing the isolation of the moment but also, in a rather lovely way, creating a sense of spaciousness.

There’s also real subtlety in Dooley’s characterisation: Toby especially, is a delight – an innocent, really, he’s a man child – loves his squash and his snacks, and still feels the draw of a child’s toy (his theft of an Intergalactic Commander from the lost property office is the cause of the argument). He’s largely oblivious to the world around him, daydreaming of stardom with his band – despite not playing an instrument. If the band doesn’t work out, he’s going to be ‘a bus driver. But for planes’ (‘a pilot’, Mr Daniels interjects drily). Toby is studying Psychology A-level in a desultory fashion and he finds it puzzling – ‘it’s mainly been about old blokes torturing monkeys’ he says, but he understands psychology intuitively and sees the loneliness behind Mr Daniels’s prickly exterior. His care for Mr Daniels prompts a rare compliment from his usually taciturn father – ‘You’ve done a good thing there, boy’, he allows, ‘I hope you know we are proud of you’.

The book’s final treat is a wordsearch for the reader in the endmatter – a nod to Dooley’s love of games and puzzles. Flake had a crossword, and this puzzle works as a similar callback. Mr Daniels has been hoarding a lost medieval collection of wordsearches, all in ecclesiastical Latin; the wordsearch duly requires … ecclesiastical Latin. There’s another puzzle earlier in the book – a jigsaw that Mr Daniels is steadily completing as new pieces arrive over time in the lost property office – and the half-formed image is shown to be very specific but entirely obscure. That both puzzles are resolutely enigmatic is fitting, a neat echo of the obscurity of Mr Daniels’ arcane theorems.

- A connection here with Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi which similarly exploits the comic potential of the contrast between antiquity and the contemporary while also creating genuinely expansive, even transcendental moments.