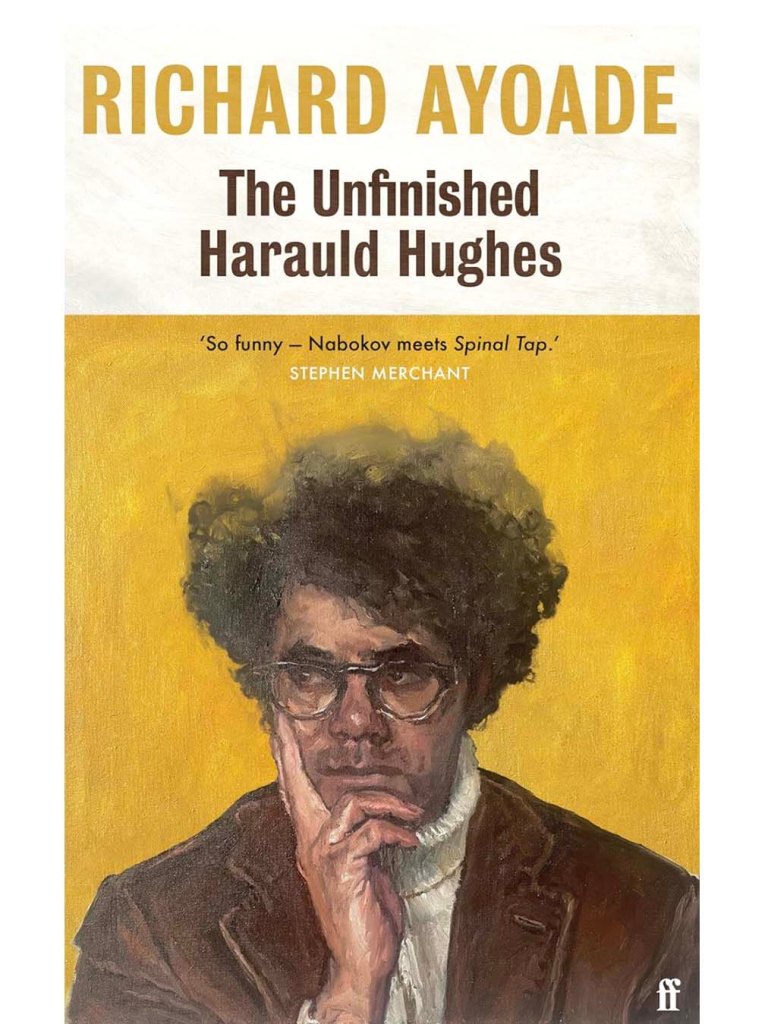

Richard Ayoade’s comic novel, The Unfinished Harauld Hughes, tracks the making of a documentary about a forgotten, Pinteresque playwright who just so happens to bear an extraordinary resemblance to Ayoade himself. It is just one piece of an elaborate, multi-faceted endeavour which also includes three volumes of Hughes’s complete works. In trying to define the project, it is Ayoade himself, always several steps ahead, who supplies an effective label – ‘absurdist postmodernism’ – this via an Esquire article, the interviewer another of Ayoade’s creations. In its complexity and variety the project is also a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – with the ‘surround-sound’ quality created by the sheer variety of mediums and typologies used: playscripts, memoirs, letters, forewords, obituaries, and cued visually with photographs and paintings of Hughes (Ayoade in brooding mode), and typography with 60s styling. For all the undoubted erudition that underpins the project, there is also a childlike sense of play in the world-building: it’s exuberantly funny, and often outright silly, and there’s real pleasure in the intersecting references. Ayoade talks about writing as a conduit for ‘being in a certain world’, and his delight in his creation is evident.

The intent is clearly parodic – capturing the self-seriousness of postwar British culture, both high and low, and satirising artistic and critical pomposity more broadly. But there’s something limiting about the classification of parody, which omits much of the project’s generative complexity; with its layered characterisation, distilled portraits of both then and now, and acute insights into the nature of literature and film. Keith Miller is right to say that ‘there’s something a shade ungenerous about parody’ (TLS), but wrong to see that lack of generosity in Ayoade’s work – like George Saunders, he renovates satire and its association with derision with a sweetness of sorts. At the heart of that sweetness is the love between Hughes, and his paramour, Lady Virginia Lovilocke. Hughes is terse, manly – and like Pinter with working class roots – while Lady Lovilocke, modelled on Pinter’s second wife, Lady Antonia Fraser, could scarcely be more aristocratic in her airy serenity.

Through interviews and critical commentary, the narrator assembles various attempts to capture Hughes’s essence, including some of the great man’s own thoughts on the matter; in one preface he proclaims with characteristic forcefulness: ‘My work as a playwright results from the images and words that rise up from my soul and spring, unbidden, into being, I can no sooner control these eruptions than I can staunch the molten spray of a volcano or one of my erections’ (Four Films xix). But the use of multiple mediums ensures the revelations about character are always somehow sidelong and the idea of an omniscient narrator feels a heavy-handed instrument in contrast. Indeed, we hear from Lady Lovilocke that Harauld, in typically peremptory style, ‘loathed the notion of the omniscient narrator. To him, all stories were unfinished, continuing to develop with each telling, each viewing..’ (99), and Ayoade shares that suspicion, his additive approach percolating through layers of narrative. He has talked about the complex web of ‘pop culture knowledge’ that we exist in, and creates a similar web effect here as the four books interact and overlap.

The layered, sideways quality is also there in the more theoretical discussions, insights from Ayoade the narrator about the nature of screenplays, for example, a form he describes as ‘little more than a promissory epistle’ (110) – are then taken up by one of Lady Lovilocke’s diary entries – relating a conversation with Harauld, who is frustrated with his experiences in writing for film and ‘tired of film being parasitic’. ‘The concept of cinema as an ancillary art is so terribly draining’ Lady Lovilocke teases; ‘You’re very beautiful when you’re facetious’, says Harauld in response. It’s theory as flirtation in true screwball style, and one thing leads to another: ‘We ask the staff to run out for croissants and extra eggs and champagne. We’ll be hungry in the morning’ (111).

The pair’s rather unreconstructed gender roles are one way in which the characters are deeply time specific – there are plenty others: director Leslie Francis, tormented by his mince addiction, an overhang from National Service; a very different creature to his rival, ‘rock star’ director Ibssen Anderssen, who ‘loved his spliff, his uppers, his ludes’ and ‘always had some dreamy-looking bird hanging around’ (38). Then there’s Harauld’s half-brother Mickie Perch and his brand of 60s gangland machismo, whose nightclubs became fixtures of the post-war London scene, combining ‘all-day fry-ups, hard bop and topless waitresses’ (23). The generation above theirs is also sketched with wit and economy: Lady Lovilocke’s first husband, Lord Langley Lovilocke – a highly decorated submarine commander during the war with a horror of intimacy (56), and whose sense of honour prompts a bluff commendation of his rival in fine Wodehousian style: ‘Well, he’s a dashed decent playwright. And a hell of a badminton player’ (105).

The contemporary characters are similarly time bound: Dan, the director of the documentary, ‘who refers to himself variously as ‘D Man’, ‘D’Man’ and ‘D Dog” (14), in a watered-down street style that captures his vacuousness. Dan insists on referring to the film as a ‘doc’ and Ayoade’s disdain for his ‘barbaric …contractions’ (89) registers both Dan’s idiocy and his own prissiness. An out and out philistine (suspicious of books, Dan calls Ayoade ‘library boy’), and aggressively casual, his vacuousness is symptomatic of a wider inanity. Filming in one of the sets for the ‘doc’, an abandoned office block, with ‘a heap of silty office chairs’ just out of shot, Ayoade and Dan watch a dramatised reading of Lady Lovilocke’s memoir on a monitor ‘next to a whiteboard on which are written the words “Always be solutioning”‘ (50). They’re watching a fictionalised version of the past, filmed through the filter of a particular conception of the past (Dan’s reductive idea of Lady Lovilocke) in the wider context of an impoverished present, characterised as crumbling late capitalism, where corporate jargon (‘Always be solutioning’) presents a form of inanity adjacent to Dan’s. Character traits and emotions tend to be seen as prior to society and culture, but Ayoade shows us that individual traits are often timebound, and socially or culturally produced.

Born to a white missionary and a Nigerian sailor, Hughes wouldn’t have been easily accommodated as a towering cultural colossus by his era, so, alongside all the other pleasures of the project, there’s also perhaps a sense of wish fulfilment in creating a counterfactual postwar history in which a working class person of colour is such a significant figure – with his race effectively not an issue. The gradual accretion of presence through primary texts and documentary evidence along with the reality effect of the book design, and even the piggy-backing on actual people – all contribute to a thickening, surround-sound effect which, while obviously absurd and equivocal, is also in service to the making up of a dreamed of antecedent.

It is commonly understood that realism makes worlds, while postmodernism unmakes them, but Ayoade’s ‘absurdist postmodernism’, profoundly self-conscious and comic to boot, conjures a world through its circumspect enchantment.

Ayoade, Richard (2024), The Unfinished Harauld Hughes, London: Faber & Faber.

Ayoade, Richard (2024), Four Films by Harauld Hughes (1970), London: Faber & Faber.

Ayoade, Richard (as Chloe Clifton-Wright) (2024) ‘Play For Today? An Attritional Interview With Richard Ayoade’, Esquire, 3 Oct,

https://www.esquire.com/uk/culture/books/a62496509/play-for-today-an-attritional-interview-with-richard-ayoade/

Miller, Keith (2025) ‘The man behind the glasses’ TLS, 7 Feb, https://www.the-tls.com/arts/film/richard-ayoade-harauld-hughes-book-review-keith-miller

The Observer (2025), ‘Richard Ayoade on his writing style, creative processes and The Unfinished Harauld Hughes’, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r7o_sqX58vE